From my early childhood Lenny Myers was my best friend as I grew up in Post-War Rushden, Northamptonshire where we had both been born. We went to South End Junior school in Rushden together. We adventured together. We caught measles and chicken pox together. We were inseparable except for the short, sulky periods following an occasional argument.

Lenny was a tubby, robust, outgoing boy in sharp contrast with me: skinny, somewhat sickly and introspective. Although rationing was still in force and we were always ready for the next meal, I don’t think either of us ever felt desperate for food or ‘deprived’. Our Mothers, having brought up our elder siblings during the war years, were absolute masters of ‘making do’ with leftovers, cheap cuts of meat and homegrown vegetables.

We shadowed each other’s lives. His family was the first to have a television set, my family was first to have a car. A perfectly natural arrangement, therefore, for me to watch the Queen’s Coronation in 1953 on their tiny, flickering screen and for him to come with me when my Father and Mother made their occasional, pioneering seaside trips to Hunstanton on the Norfolk coast carrying jerrycans of water for the car’s radiator. On the return journey we always stopped on the Sandringham estate to brew a pot of tea over a methylated spirits stove.

Even at the age of 82 I still have clear memories of those seemingly endless Summer holidays when we roamed far and wide into the Northamptonshire countryside biking for miles on country roads with their then sparse and slow-moving traffic. We didn’t know the word “trespass” and wouldn’t have cared if we did. We built dams in the brooks and streams and we discovered and rejoiced in the freedom and the sheer joy of pointless ‘messing about’.

We built rough shelters in the woods, climbed trees and swung from their branches, paddled in muddy streams and built rafts, miraculously surviving perilous trips across a flooded sandpit. Special holiday highlights depended on persuading my Father to drive us to where we could swim or paddle around in a ‘government surplus’ rubber RAF survival dinghy on the then unpolluted river Nene. Another favourite swimming spot on the Ouse just over the border in Bedfordshire.

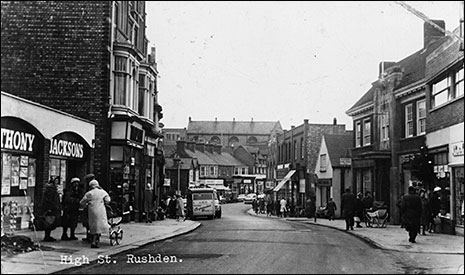

And how did we survive careering around the town on our bikes, proudly giving incorrect hand signals–often on the wrong side of the road. We would not have got through childhood in today’s traffic. Even during school time we found ways of adventuring in the local Hall Park – always keeping an eye open for Tom, the bad-tempered park keeper who would chase us away, cursing wildly if he heard us in the woods away from the made up paths and seating areas.

Then in 1953 there suddenly came something called the “11-plus” examination. Nobody explained just how important this milestone event was and the extent to which it would determine our futures. Indeed, I don’t think even our parents knew its significance. Lenny and I were happily oblivious to the fact that it would eventually bring our friendship to an end.

Only after the examination did we learn that it decided where we went for the next stage of our education and hence the possible career paths which would be open to us. Amidst great confusion and unease, we learned that our performance in this examination determined which of two paths our secondary education would follow. If we failed this thing called the 11-plus we went on to something called a Secondary Modern school where, in addition to a basic education in mathematics, science and English, we would concentrate on acquiring practical skills such as woodwork, metalcraft and home economics; whereas if we passed we would go to a Grammar school where we would study more academic subjects like English literature history, geography and modern languages.

And little did we know or even suspect how the results would impact Lenny and me.

My results were borderline but, after interview, I passed the examination and started at the Grammar School a five-mile bus ride away. Lenny didn’t pass so he went to the Secondary Modern school in the town where we lived. Of course, I realise now that it was inevitable that our time together would become more limited and, as we grew up, our adventures fewer. We began to adopt different circles of friends. Our interests began to differ and our conversations became less comfortable and easy. From being intimate companions sharing life through six or seven years of formative childhood, we drifted gradually into becoming separate people with different attitudes and outlooks.After a couple of years of increasingly rare contact came the unthought of, unrealised fateful day when I saw him for the last time.

Of course, neither of us realised that it would be the last time. We probably parted with a careless “Cheerio” and away we went down our separate lifetime paths. If only I had known that was to be our last meeting, the end of our intense boyhood friendship – the end of our childhoods. How would I have dealt with the enormity of what was happening to us at that final parting? How could I possibly have explained what our years of friendship had meant to me? How would we both have coped with the end of a companionship which had steered us through childhood and given us, unrealised at the time, such vital formative experiences?

I suppose this was simply the inevitability of growing up and perhaps it didn’t matter that this was to be our last day together so it was for the best that we didn’t know. But it doesn’t feel that way. It feels as if we should have done, or said, something to mark the enormity and sadness of the occasion. I wish I had known that we were parting for the very last time and that my boyhood friendship with Lenny had served its purpose and had come to a natural end. I wish I could have told him how much our experiences together had meant to me, how they had influenced my development and, simply, what a grand time we had had growing up together.

I wish I’d known.

********

Every stranger we encounter has lives as vivid as our own. In our Pages From A Diary column we bring you personal histories of these strangers, both significant and modest.