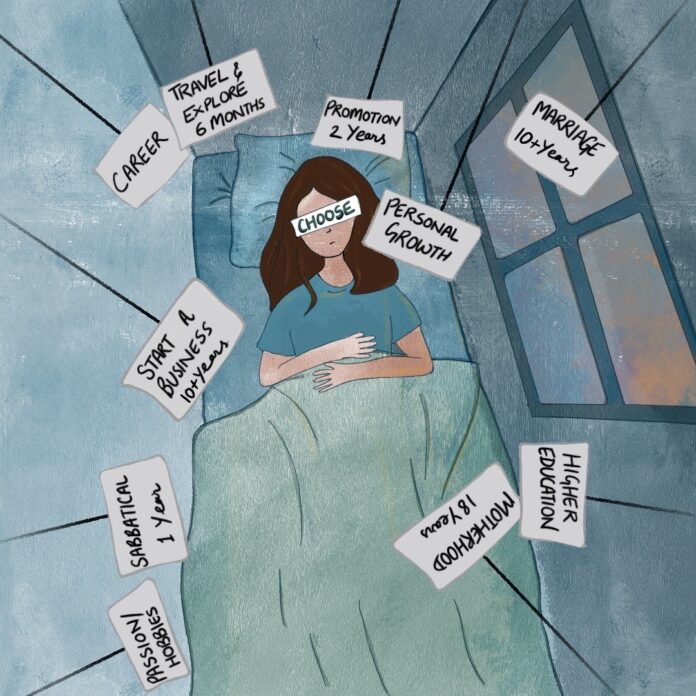

In the collaborative game of Hanabi, players work together to create vibrant fireworks in 5 different colours, caught between moments of joy and panic as the clock runs down. Together, they can earn back timer counters, buy more time and continue to build their spectacle of pyrotechnics. When the birth control pill was approved for prescription in the US and Europe in the 1960’s, for the first time women wishing to be mothers were given access to their own timer counters; time to explore and build a career, time to be free intellectually, sexually, financially. As time begins to run out and the potential prospect of motherhood draws closer on the horizon, we consider our options to win more time, to beat the clock or even opt out of the race altogether.

In my early twenties time felt like an endless expanse stretched out ahead of me. I had infinite opportunities and choices at my fingertips, I could follow a meandering curiosity one day and then just as quickly follow another without any serious or irreversible consequences. Motherhood was a door that was always open in the distant future, it would be ready and waiting for me, all I needed to do was knock. I knew that I had a strong maternal instinct by my early teens, delighting in the infectious joie de vivre of young children and succumbing to the soothing feeling of holding a baby in my arms whenever the opportunity presented itself.

Having been acutely tuned into this biological inclination for over 15 years, becoming a mother felt like a foregone conclusion, so truthfully I never stopped to interrogate my own decision making process, because I didn’t have one. I was sailing to a point on the horizon out of habit under the assumption that I would end up there eventually. Until I met someone who doesn’t know if they want kids. For the first time I was compelled to confront the forces behind my internal compass, to thoroughly dig into the realities of a life with children and a life without. Feeling quite aware of the many joys of having children and the unfathomable love that parents speak of, I started by writing a list of all the positives of not having children. I hit 30 in under 5 minutes.

Top of the list, not having to choose between my career and motherhood. Beyond the classic trade off of temporarily putting my career on hold to have a child and reckoning with an earning penalty as well as navigating a return to work, I’m thinking in particular of the the daily choices working mothers face trying to balance the demands of their job with the demands of their domestic life; responsibilities as a mother, a caregiver, a partner. Some women decide the juggling act isn’t for them and choose full-time motherhood, the number of women going down this route is increasing and in recent years the ‘Tradwife’ phenomenon has emerged, essentially the rise of an ultra conservative, ultra traditional house-wife. I respect every woman’s right to choose the path that suits them, there is no authentic brand of feminism that undermines or sneers at another woman’s life choices. For myself, having been raised single handedly by a mother who took to juggling parenting and working with a fierce determination that was the unwavering backdrop of my childhood, it is simply not an option for me to bring a child into this world and be dependent on someone else for that child’s quality of life, let alone my own.

So working motherhood it is. In all its glory. First I’ll need to embrace and accept the realities of an earning penalty, sometimes referred to as the child penalty. In a paper investigating employment trends for men and women in 134 countries, LSE Professor Camille Landais’ data analysis concludes that the child penalty is responsible for more than 80% of the gender pay gap in wealthy countries. Before having a child the employment trajectory of men and women follow parallel paths but after the first child is born the woman’s employment rate and earnings decline, “women never fully recover from that massive impact.”

In order to offset the effects of the child penalty financially and professionally, the later you have children the better, but biologically and physiologically the earlier you have children the better. Timing is everything, yet the further along the tightrope I walk the less sure I am of which sacrifice I want to make, if any at all.

So in the absence of certainty I consider buying myself more time, egg freezing is really the only option on the table if you want to have biological children. I am optimistic but having worked in female-health for three years I know the process is expensive and isn’t a guaranteed insurance policy. Yes, I increase my chances, though the odds are completely dependent on how many eggs I freeze and the age at which I retrieve them.

Our fertility peaks in our early to mid-twenties and then drops off in the following years. And so the best time to freeze your eggs is in your late twenties to early thirties, ideally before 35. The average number of eggs retrieved per cycle is 10-20, say I retrieve and freeze 12 eggs, 75% of those will survive thawing (9), 75% of those will be successfully fertilised (6), then one or more of these may be unsuitable for transfer or may be discarded during chromosome screening. So 4 fertilised eggs left for implanting. 4 chances for a successful pregnancy. I can do a second cycle to double those odds, at a cost of €3.700 per cycle plus €500 for each year of storage. If I freeze two cycles of eggs next year when I am 30 and thaw them at 36 with a further cost of €2000-3000 for in vitro fertilisation the total cost is around €12,500 in the Netherlands. The odds of having a child after injecting myself with hormones twice a day every day for ten days, then going under general anaesthesia for retrieval on two separate occasions and shelling out €12,500? Somewhere in the range of 33% and 51%. It’s not a small sum, more than half my savings, but I’ll take those odds, I consider myself to be a relatively lucky person and believe that what is meant for me will not pass me by. Yet in the same breath my rational mind puts my spirituality on pause for a moment and snaps me back to reality; having children is not a serendipitous act of the universe, you walk through that door and you leave everything as you know it behind.

Having witnessed my mother sacrifice sleep, romance, a social life and self-care for the role of mother and father I am under no illusion of the toll motherhood will take. As my list grows day-by-day and I continue to collate the positives of a child-free life I stumble across the ‘child-free by choice’ discourse, on TikTok where else? Countless women in their twenties, thirties and forties sharing the peace, joy and possibilities of lives without kids; of sleeping in on the weekends, reading for hours on end, being immersed in creative hobbies, having financial security, being debt free, travelling endlessly, revelling in spontaneity and still being deeply in love with their partner. Of course these all sound like the hallmarks of a good life but the stories that leave a lasting impression on me are the accounts of being part of the village for friends and family with children. These women are on site for afternoons in the park, rainy days drawing, painting, water fights, movie-nights, bedtime stories, they have the precious time to offer to the parents who live in a constant deficit.

These moments are the parts of motherhood I know I would miss, the younger years when they are full of wonder and magic. I love kids, I love their brutal honesty, the imaginative tales they share, I love being sworn into secrecy, being a partner in crime, mischievously stomping through the world with reckless abandonment. I think I could happily forgo the pre-teen years, the teenage years, the year where they slam their bedroom door so often you have to take it off its hinges and put it in the garden shed (sorry, mum!). But being there for the women who have held my hand through the trials and tribulations of young adulthood whilst they navigate motherhood, that intuitively feels like a fulfilling way to share my time in a hypothetical future where I am child-free.

The truth is I have no idea what the future holds for me, for us or if I’ll ever be ready to sacrifice the freedoms and luxuries of a life without kids, or if anyone is ever really ready. Maybe we’ll have children and inevitably embrace the chaos and beauty of making a tiny human the centre of our universe, or maybe I’m destined to be the perpetual godmother and favourite aunt who is suspiciously rich and gets 8 hours of sleep, every single night.

Emma Holmes is a British writer living in Amsterdam with a passion for cultural discourse on modern womanhood, an inherent love for French cinema, Scandinavian pastries, and astrology.